The Clockwork Muse: The Predictability of Artistic Change (1990)

Author (publications)

Colin Martindale (March 21, 1943 – November 16, 2008) was a professor of psychology at the University of Maine for 35 years.

Martindale wrote and did research analyzing artistic processes. His most popular work was The Clockwork Muse (1990). Martindale argued that all artistic development over time in written, visual and musical works was the result of a search for novelty.

Martindale was awarded the 1984 American Association for the Advancement of Science Prize for Behavioral Science Research.

Overview

Although he idea of Digital Humanities, or the quantitative analysis of the arts, is starting to make its presence felt in the last half of the 2010s, The Clockwork Muse predates all this by decades. Martindale was doing computational analysis of poetry, prose, visual arts, architecture, and even scientific writing in the 1980s!

The central premise of this book is that human creative output is driven by what he calls The Law of Novelty, which consist of two components:

- Arousal potential

- Habituation, or exposure fatigue

His main premise is that to be successful, arousal potential must increase over time, and at a rate that the audience desires. Too little, and the audience will become fatigued and find novelty elsewhere. Too fast and the audience won’t comprehend. Artists that produce novelty at the right rate for their communities are the most successful. At the same time, artists behave according to the principle of least effort, and will take the easiest path to increasing arousal potential.

How art is created for human audiences is by varying the ratio of two approaches:

- Primordial content: This represents a “going back to basics” approach to art. Forms become simpler and less refined. Increases in primordial content typically occur at the beginning of a movement. Consider impressionism, where art went from highly refined representation to vaguer representations that incorporated a larger interpretive and emotional component.

- Stylistic change: This is the process that we see within an artistic movement, where the process is incrementally refined by the artists in the movement. A syntax is developed, and a progressively more sophisticated “conversation” emerges.

The contribution of these two approaches in art movements, careers, and even within sequential art such as novels and music vary inversely to one another in roughly sinusoidal patterns. While each value may decrease individually, the combination of the two increases.

Martindale then goes on to show that this theory holds in a multitude of contexts and studies. There are two general forms of the studies. In his text analytics, he analyzes variability/incongruity, and groups terms into “Primordial”/”Stylistic” buckets and then does statistical analysis on the results, generally finding good correlations. For the study of visual arts ranging from painting to architecture, he collects canonical images across a given timeframe (often in centuries), divides this span into segments, randomises the segments, and has subjects classify the images across multiple dimensions which in turn can be collapsed into the primordial/stylistic overarching categories.

My more theoretical thoughts

The dichotomy of primorial content / stylistic change matches Kaufman’s concepts of long jumps / hillclimbing on rough fitness landscapes, and also Iain McGilchrist’s interpretation of the roles of the left / right hemispheres of the brain in the The Master and his Emissary, where the right hemisphere operates in global, general contexts and the left is local and specific.

Stylistic change depresses the hill it is climbing. That’s why large jumps in the fitness space represented by increased primordial content work – Once a movement is exhausted, a small jump will only sink the terrain further. But a large jump is almost guaranteed to increase arousal potential.

People (and other organisms?) get bored with incremental progress below a certain rate (Habituation), and become biased towards long jumps that create change and provide novelty. There is survival value in this that is addressed in the explore/exploit paradox. This pressure for change at a certain rate is what drives much of our clustering behavior, which is based on alignment. Insufficient arousal builds up greater potential for nonlinear long jumps, or revolution.

Speed affects the ability to change direction. Changing direction stylistically can create more arousal potential than the linear extension of a particular technique (Though reversing direction should lower arousal potential). That means the faster that stylistic change is happening, the more likely that progress will be linear (realism -> superrealism -> hyperrealism, etc)

Notes

Chapter 1: A Scientific Approach to Art and Literature

- As for history, the whole point of universal history is to find general laws that apply no matter what nations are involved or at what time. Because the topic is complex, these laws seem less deterministic than those governing objects falling in vacuums. History is, however, not completely chaotic and unpredictable. Just as in chemistry, certain combinations in certain situations will explode. Just as in physics, certain configurations in certain places will collapse. (Page 15)

- Styles going by different names show obvious similarities: for example, eighteenth-century neoclassicism and fifteenth-century renaissance style, and fourteenth-century gothicism and nineteenth-century romanticism. Though the earlier style ~ did not directly cause the later style, we must explain the similarities. Perhaps art oscillates along a continuum so that such similarities are inevitable. If so, we must explain why it oscillates, and why along that continuum rather than along some other one. Of course, we must explain what the continuum is and why it exists. (Page 20)

- The psychologist D. T. Campbell (1965) argues for direct application of the principles of Darwinian evolution to cha11ge in cultural systems and products. Sociocultural change, he says, is a product of “blind” variation and selective retention. The three necessities for evolution of any sort are: presence of variations, consistent selection criteria that favor sorne variants over others, and mechanisms for preserving the selected variants. At any time, a number of variants of a given object are produced, and the n1ost useful, pleasing or rewarding arc chosen for retention. Then, at the next point in tirnc, there is variation of the new form, and the process continues. Though such theories provide a general framework for thinking about aesthetic evolution, they do not tell us why aesthetic variation exists in the first place, nor were they proposed to do so. (Page 33)

Chapter 2: A Psychological Theory of Aesthetic Evolution

- Theories concerning an inner logic driving change in the arts were anticipated by Herbert Spencer’s quasi-Darwinian theory. This English philosopher, in his major statement on art (1910 [1892]), set forth the principle that art, like everything else, moves from simple to complex. By complex, he meant more differentiated and hierarchically integrated. The anthropologist Alfred Kroeber (1956) followed Spencer in proposing such a simple-to-complex law, as did Kubler (1962). (Page 31)

- If you drop an object in a vacuum, gravitation will cause it to move in a specific direction at a specific rate. Just so, if art were created in a social vacuum, pressure for novelty would cause it to evolve in a specific manner The empirical evidence suggests that art tends in fact to evolve in a social vacuum, and that non-evolutionary factors are comparatively negligible Though art is not produced in a complete social vacuum, I believe there to he more of a social vacuum than is commonly thought. Furthermore, social forces are analogous to friction, in that they impede or slow down the progress of an artistic tradition. (Page 34)

- In the case of biological evolution, selected variations are, of course, encoded in the “memory” of DNA configurations. We may assume that more important or more complex DNA configurations are “forgotten” less quickly than less complex ones. The analogue is most certainly the case in the arts. If for no other reason than our educational system, the average reader of a contemporary British poet has some rudimentary “memory” of the poet’s predecessors at least back to the time of Chaucer. In comparison, the average person who purchases clothing has a poor memory for prior styles of fashion. As likely as not, such a person knows little about the styles of even thirty or forty years ago. The better “memory” of the poetic system leads us to expect that it should change in a different manner than fashion. In the latter, novelty seems often to be obtained by reviving a forgotten style, an option not as available to the poet. (Page 37)

- …no one liked the Moonlight Sonata, he did not understand why the person was bothering with such chitchat. It did not concern Beethoven what people thought of that sonata. He did not write it for others. He wrote it for himself, and he liked it. As I have said, the notion that an artist is trying to communicate with an audience is misleading. It leads to an “audience-centric” confusion. (Page 38)

- This book is about how Nomads work. High art has to be exclusively Nomad, and in most cases, drives the audience away. Pop art is different, because it cares about the audience.

- A good deal of evidence supports the contcnhon that people prefer stimuli with a medium degree of arousal potential and do not like stimuli with either an extremely high or low arousal potential. This relationship, described by the Wundt curve, is borne out by several genera) studies reviewed by Theodore Schneirla ( 1959) and Berlyne ( 1967) as well as by studies 0f aesthetic stimuli per se. The effect has been found with both literary (Evans 1969; Kamann 1963) and visual (Day 1967; Vitz 1966) stimuli. There is some question about the shape of the Wundt curve (Martindale et al. 1990 ), but there is no question that people do like some degree of intensity, complexity, and so on. (Page 42)

- Hedonic tone and arousal potential. According to Berlyne (1971), hedonic tone is related to the arousal potential of a stimulus by what is called the Wundt curve: stimuli with low arousal potential elicit indifference, stimuli with medium arousal potential elicit maximal pleasure, and stimuli with high levels of arousal potential elicit displeasure. (Page 42)

- Habituation refers to the phenomenon whereby repetitions of a stimulus are accompanied by decreases in physiological reactivity to it. The psychological concomitant is becoming used to or bored with the stimulus. Habituation is not merely the polar opposite of need for novelty. Avoiding boredom is not necessarily the equivalent of approaching novelty. People who habituate quickly to stimuli do not necessarily have a high need for novelty (McClelland 1951 ). In fact, creative people like novelty but habituate more slowly than do uncreative people (Rosen, Moore, and Martindale 1983). Because of this fact and because habituation seems to be a universal property of nervous tissue (Thompson et al. 1979 ). (Page 45)

- Ambiguity is a collative variable. Collative properties such as novelty or unpredictability can vary much more freely than meaning in all of the arts. One soon finds that to increase the arousal potential of aesthetic products over time, one must increase ambiguity, novelty, incongruity, and other collative properties. This is the reason for my theoretical emphasis on collative properties rather than upon other components of arousal potential. (Page 47)

- Peak shift is a well-established behavioral phenomenon (Hanson 1959). Consider an animal that is rewarded if it responds to one stimulus (such as a 200-Hz tone) and not rewarded if it responds to another stimulus (a 180-Hz tone). After training, the animal will exhibit maximal responsivity at a point beyond which it was rewarded and in a direction away from the unrewarded stimulus (a 220-Hz tone). J.E.R. Staddon (1975) argues that peak shift serves as the force behind sexual selection in biological evolution. Because of peak shift, female birds that prefer to mate with males with bright rather than dull plumage will show even greater preference for males with supernormal or above-average brightness. As a result, such males will mate more often and produce more offspring. As a further result, and because peak shift operates during every generation, the brightness of male plumage in the species will increase across generations. (Page 47)

- On the psychological level, habituation occurs gradually and the need for novelty is held in check by the peak-shift effect. Thus, an audience should reject not only works of art with insufficient arousal potential but also those having too much. Finally, the principle of least, effort assures us that artists will increase arousal potential by the minimum amount needed to offset habituation. The opposing pressures should lead to gradual and orderly change in the arts. (Page 48)

- Berlyne ( 1971) pointed out that the evolutionary theory has difficulty in explaining cases such as Egyptian art that show extremely slow rates of change. Yet, though much Egyptian painting was sealed in tombs-hardly a place to bring about speedy habituation-it did evolve as predicted by the theory (see pages 212-19). In general, the more an audience is exposed to a type of art, the faster the art should change. This assumption leads to specific predictions: we should find higher rates of change in living room furniture than in bedroom furniture, in everyday dress than in formal dress, and so on. (Page 52)

- A simpler explanation is that clothing can lose some of its aesthetic qualities because of functional reasons. Fashion is not a high art. There is a pressure to increase arousal potential, but other pressures can add so much noise that the theory of aesthetic evolution is only marginally — rather than continually –applicable. Consumers can retard change by passive resistance. They can extinguish styles altogether by boycott. Walking sticks and hats are more or less extinct. The audience did this. This fact does not refute the theory of aesthetic evolution. Evolution can occur only when the environment permits it. If a politician kills all the poets, poetic evolution obviously ceases. If poets had to make a living by writing poetry, there would be no poetry; it would have gone the way of the scarlet waistcoat. On the other side of the coin, if the makers of scarlet waistcoats had not held to the silly notion that the only thing they are good for is to wear, there would still be plenty of them , and they would be quite fancy. Their functional aspect put all kinds of constraints on what they could look. like. Recall Kubler’s definition that if something has a use, it is not art. If something has a use, people want it to work. That gets in the way of its aesthetic aspects. If something has a use, people can stop using it and destroy its aesthetic aspects altogether. Being useless has distinct advantages. Paintings don’t come with warranties. Customers can’t return them and say they don’t work–or that they have suddenly started to work. Customers can’t say anything, really. If something is useless, it doesn’t make any sense to say how long it will remain useless or to quibble about exactly how it should be useless. (Page 55)

- The evolutionary theory can be construed in two ways. The weak version is that the theory explains a bit, but perhaps not much, about art history. The strong version is that the theory explains the main trends in art history. Because the main axes of artistic style-classic versus romantic, simple versus complex-are isomorphic with the main theoretical axes-conceptual versus primordial content, low versus high arousal potential– it is not unreasonable to think that the strong version may be true. (Page 69)

Chapter 3. Crucible in a Tower of Ivory: Modern French Poetry

(Page 104)

- We know that the truth must lie somewhere between these two extremes: that is, We know that poets cluster together into groups-for example, some tend to write lyrical poetry, whereas others write epic poetry. We want to know how many dimensions are needed to account for the similarities among poets. Fortunately, once we have correlated all of the poets with one another, a procedure called multidimensional scaling will tell us just this. Multidimensional scaling (Scikit-learn) tells us that the twenty-one French poets differ along three· main dimensions. These three dimensions account for 94 percent of the similarity matrix. (Page 114)

Chapter 4. Centuries of British Poetry

- When a poetic tradition is first coalescing, poets are less sure of the rules of the game and of who else is playing. (Page 123)

- I think this is the case for most if not all group consensus under uncertainty. I see this a lot in the D&D data.

- Thus, legislators are really under pressure to produce new combinations of words, called laws, just as are poets. Suppose Parliament enacts a set of far-reaching new laws (initiates a new style). Subsequent Parliaments are going to have to pass laws that elaborate upon and refine the general laws. Eventually the result is going to be a set of overly specific, complicated, and contradictory laws. At this point, another stylistic change is in order: that is, a new set of general laws. These laws will also need refinement, so the whole process will begin anew. If this is at all close to capturing what legislative bodies do, then we might expect oscillations in primordial content because of oscillations in generality versus specificity of laws- an argument that cursory reading of the British statutes does support. General statutes are often followed by more concrete and specific ones that clarify the earlier statute or limit it so as to prevent unintended consequences. On the other side of the coin, a variety of specific statutes may eventually be replaced by an overarching general law. If we had a more appropriate measure of impact or complexity, we would almost certainly find that the complexity of law has increased across time. In an abstract sense, then, legal and poetic discourse are subject to evolutionary pressures that are isomorphic. (Page 131)

- The amount of primordial content in the two prior periods is negatively related to primordial content in a given period. The amount of stylistic change is positively related to stylistic change in the prior period and negatively related to stylistic change two period earlier. These influences of the past on the present set up oscillations. (Page 141)

- The delay in the connections may matter a lot. There may have to be a graph matrix term included in the chain. Behaviors would be very different for a fast, low weight link and a heavy weight, delayed link. Or is that a property in the reactivity of the node? Or both?

- Primordial content shows a significant linear increase across all four periods. This linear trend accounts for 59 percent of the overall variability in primordial content. There is no sign of leveling off of this trend during the later periods. The pattern of results is most consistent with the hypothesis that the late metaphysical poets were caught in an evolutionary trap: They engaged in deeper and deeper regression, but did not achieve the desired increases in arousal potential. Once entrapped, the metaphysical style perished and was replaced by the ensuing neoclassical style. (Page 148)

- I think this is a case where the “elevation” of the fitness landscape is sinking, but the practitioners are hillclimbing the wrong way.

Chapter 5. On American Shores: Poetry, Fiction, and Musical Lyrics

- I have been talking, I know, in rarefied or abstract terms, our 170 poets ending by being represented by points in four – or five-dimensional hyperspaces. It is where they are in these abstract spaces that I have aimed to account for by four or five equations. The exciting thing is that poetry moves through these spaces in very orderly ways across the course of time and I think we can eventually capture the beauty of this sweep of history with quite simple and beautiful equations. Of course, this is hardly the usual way of talking about the history of poetry. However, I think that it adds to or complements-rather than in any way contradicting or negating-the more usual approaches. (Page 152)

- To see how much of the overall variability in poetic language the evolutionary theory accounts for, I followed the same procedures that were used for French and English poetry. I first intercorrelated the poets’ profiles on the Harvard III categories to measure their relative similarity. Then, through multidimensional scaling, I found that four dimensions accounted for 94 percent of the variation among the poets. Correlating these dimensions with the content categories suggests that the dimensions arc getting at lyric, narrative, and two sorts of emotional modes. We can account for 25 percent of variation in this space with our theoretical variables-a good bit less than the figure for French and British poetry. One reason for this discrepancy may be that the American series contains more minor poets-who may not really have a good sense of tradition than do the French and British series. They may be perfectly fine poets, but their concerns may be tangential to those of poets writing in the focal American tradition. In fact, if we examine only the four most eminent poets for each period, 43 percent of the similarity among them can be accounted for by the theoretical variables-about the same figure as for French and British poetry (Page 165)

- American poets are/were more nomadic?

- …you can’t make money writing poetry, the poet has considerable freedom: nothing he or she writes is going to make money, so there is no sense in trying. Unfortunately, the case is different with fiction. You can make money with it, but only if a lot of people like it. Publishing firms publish poetry for prestige, but they want to make a profit with fiction. They resist publishing fiction that no one will buy. This situation puts something of a non-evolutionary pressure on the writer. Even worse, the writer may want to make money and thus write more for an external audience and less for other artists. Of course, the external audience habituates and wants novelty. However, it must habituate more slowly than artists because it is exposed less frequently to literature than they. The real problem with the external audience is that it may place all sorts of non-aesthetic pressures on literature. If the audience takes a puritanical tum, it won’t read pornography. If it gets obsessed with abolishing slavery, it wants Simon Legree stories. If the audience’s desires get really extreme, the environment will be distinctly unfavorable to aesthetic evolution. To use a biological analogy, sexual selection can proceed only in a benign environment. In an environment with a lot of predators, birds of paradise could not have evolved, for their brilliant plumage would have attracted those predators. (page 169)

Chapter 6. Taking the Measure of the Visual Arts and Music

- After establishing that subjects agreed in their ratings, I obtained a mean score for cach painting on each of the variables by collapsing across subjects. The rating scales were subjected to factor analysis to see whether the scales were measuring, as hoped, a smaller number of underlying dimensions. Factor analysis (tutorial), which represents similarities among scales in a multidimensional space, indicated that the scales were really measuring five axes or dimensions. It was clear that two of these factors were, as hoped, getting at the theoretical variables. One factor-referred to as arousal potential-had high loadings on the scales Active, Complex, Tense, and Disorderly. Another-referred to as primordial content-had high loadings on Not Photographic, Not Representative of Reality, Otherworldly, and Unnatural. (Page 188)

Chapter 7. Cross-National, Cross-Genre, and Cross-Media Synchrony

- This gives us a closed circle. When the longer series of French and British painting was considered, it was clear that French painting influences British painting more than vice versa. Now we see that American painting is predictable from British painting. Closing the circle, l found French poetry to be at least synchronously related to American poetry Painting seems to be a much more international enterprise than poetry. At least for the last two centuries, British, French, ancl American painting appear to be closely related even when we take statistical precautions to avoid spurious findings. The Italian, British, and French series overlap for several periods. (Page 240)

- According to Berlyne (1971), a work of art has three types of properties: psychophysical properties intrinsic to the stimulus (such as pitch, hue, intensity), collative properties (such as novelty, complexity, ambiguity), and ecological properties (such as denotative and connotative meaning). Berlyne held that these properties taken together determine the arousal potential of a work of art. Each of these aspects of a work of art offers several possibilities for cross-media correspondence. The psychologist S.S. Stevens (1975) showed that cross-modal matching on the intensity dimension is reliable. Another psychologist, Lawrence Marks (1975), showed that there are reliable consistencies in the matching of the brightness of colors and the “brightness” ( defined by pitch and loudness) of sounds. Collative variables (such as complexity or novelty) are clearly defined across all media. Kenneth Burke ( 195 7) argued that cross-media styles are based on two dimensions that Berlyne would call collative variables: unity and diversity. Meaning can also serve as the basis for cross-media styles-as is obvious in art forms having specific content, such as representational painting and sculpture. In terms of connotative meaning, Charles Osgood, George Suci, and Percy Tannenbaum’s (1957) three factors of evaluation, potency, and activity show up in a variety of rating tasks irrespective of what is being rated. Thus, connotative meaning could serve as a basis for equating works in different media. Finally, overall arousal potential or resultant liking (see figure 2.1, page 42) could serve as a basis for cross-media styles. I have argued that it makes sense to talk about primordial content in all of the arts. The experiment I did with Ross and Miller (1985) suggests that this cross-media effect is more than giving the same name to different things. In our experiment, people wrote fantasy stories in response to paintings. Primordial content in the stories-as measured by content analysis-was correlated with primordial content-as measured by rating scales-in the paintings. (Page 251)

Page 254

- Thus, artistically untrained subjects do show a clear and significant tendency to perceive cross-media styles. Both baroque and neoclassical styles differ from the romantic style on the first dimension: that is, people see baroque and neoclassic styles as being similar to each other and dissimilar to the romantic style. Baroque and neoclassical styles do not differ significantly on this dimension. The second dimension differentiates baroque and neoclassical styles and, to a lesser extent, neoclassical and romantic styles. Baroque and romantic styles do not differ significantly on this dimension. Thus, people see baroque and romantic styles as similar to each other and dissimilar to the neoclassic style on this dimension. In summary, people perceive the three styles as varying in two fundamental ways, or along two dimensions. Unfortunately, multidimensional scaling does not tell us how to label these dimensions. (Page 255)

Chapter 8. Art and Society

- Marxism ultimately attributes much social and cultural change to the emergence of new technology: technological innovations create new means of production; a class struggle ensues for control of these means of production. (page 264)

Chapter 9. The Artist and the Work of Art

- I have argued that the effect of the pressure for novelty arises not so much from its strength as from its persistence. In the first part of this chapter, I investigate whether the pressure for novelty is strong enough to affect individual artists. Does the evolutionary theory help us understand only the great sweep of history, or can it shed light on stylistic development in the individual artist? Studies of creators as diverse as Beethoven and Grieg, Picasso and Rembrandt, and Dryden and Yeats suggest that the evolutionary theory is, indeed, relevant to the individual artist. At the end of the chapter, I report on some quantitative studies of nonevolutionary forces, such as temperament and psychopathology, that also shape the content of poets’ verse. In the middle part of the chapter, I turn quantitative methods upon individual works of art, ranging from prose through poetry to music. We find coherent trends across the course of literary narratives-trends that arise, in part, from a need to keep the reader’s attention but, in larger part, from what an author is trying to say. In fact, the type of trend we find sheds valuable light on what an author is–consciously or unconsciously-trying to say. (Page 284)

- Aesthetic evolution shows a surprising self-similarity under magnification: when we examine the course of primordial content across centuries, we find long-term trends with superimposed oscillations. If we examine the course of primordial content across the career of an individual artist, we see exactly the same thing on a smaller time scale. Theoretically, these patterns are caused by the need to increase arousal potential. This need is caused by habituation: the audience-and the artist-tires of old forms and wants new ones. Habituation corresponds, as I have said, to building up a set of expectations. After these expectations are well developed, a work of art that conforms too closely to them will elicit neither interest nor pleasure. It is to avoid this sad fate that the artist must increase the arousal potential of his or her works. (Page 312)

- On the psychological level, the theme of the journey to hell and back hypothetically symbolizes a regression from the conceptual (abstract, analytic, reality-oriented) thought of waking consciousness to primordial (concrete, free-associative, autistic) thought and then a return to conceptual thought. Of course, the psychoanalyst Ernst Kris (1952) holds that any act of creation involves an initial stage of inspiration and a subsequent stage of elaboration. In the inspirational phase, there is a regression toward primordial thought, whereas in the subsequent elaboration stage there is a return to analytic thinking. The inspirational stage yields the “rough draft” of the creative product, whereas the elaboration stage involves logical, analytical thought in putting the product into final form. Thus, the theme of the night journey mirrors the psychological processes involved in the creation of art. (Page 314)

- If a narrative describing a journey to hell or a similar region symbolizes . regression from a conceptual to a primordial state of consciousness and a subsequent return to a conceptual state, we might expect that words indicating primordial content would first increase and then decrease in the narrative. (Page 315)

- These two passages from page 333 describe earlier concepts of “coordinate frames” that we have used (in western society only?) to position imagination:

- The names will be different, but the idea is the same Since Galen’s theory of the temperaments was good enough for Kant, Wundt, and Pavlov, I’ll just use the old terms. The idea of temperament theory is that people differ along two dimensions: sanguine (optimistic and happy) versus melancholic (pessimistic and anxious) and choleric (active and quick to anger) versus phlegmatic (calm and passive) Galen connected the temperaments with bodily fluids which were seen in turn as expressions of the four elements: air versus earth and fire versus water. A nice theory, but it turned out to be wrong on the level of physiology and physics. Maybe, though, the connection between elements and temperaments is right on the psychic level.

- At least in states of fantasy and reverie, there is a correspondence between temperaments and elements. As the literary critic Northrup Frye put it, “earth, air, water, and fire arc still the four elements of imaginative experience, and always will be” (Bachelard 1964, p. vii [1938]).

Page 335

Chapter 10. Science and Art History

- To test these predictions, I had eighteen subjects rate their liking for the Italian paintings shown in chronological order and seventeen subjects rate them when shown in reverse chronological order (Martiudale 1986a). To disguise the real purpose of the experiments, the Like-Dislike scale was embedded in a set of seven other scales. Since subjects showed highly’ significant agreement in their preferences, a mean preference rating was computed for each painting in both experiments. As predicted, the correlation of liking with order was insignificant for the chronological group. On the other hand, it was strongly negative — much more so than when the paintings were shown in a random order-for the reverse-chronological group (Page 341)

- Good discussion on methods

Page 343

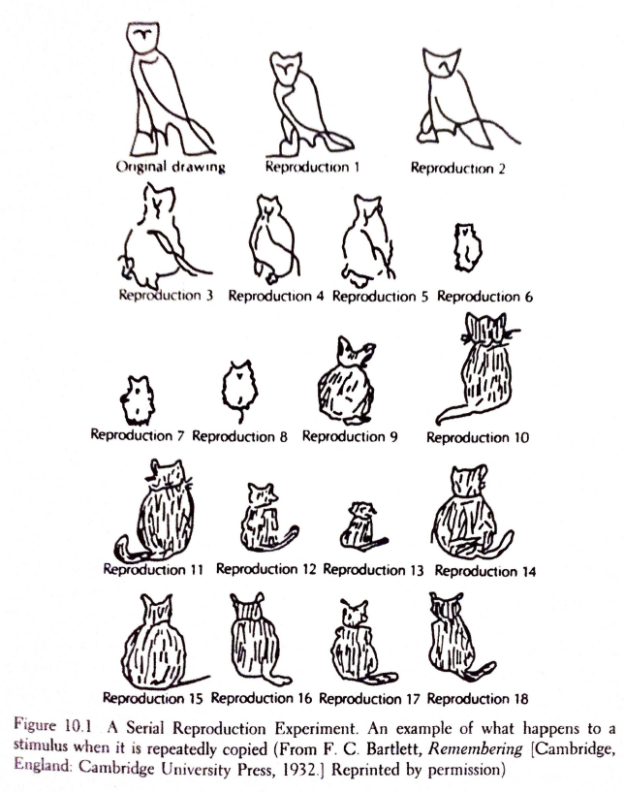

- A really interesting element to consider is how the transformation from owl to cat differs from “morphing” to latent-space interpolation. Morphing is a dissolve that includes control points for an animated transition that typically involves input from users (e.g. the animator). Latent space interpolation lacks human involvement and creates images from that latent space that would probably be outside of human cognition:

- Should we conclude from the changes in primordial content that the later drawings were made in more primordial states of mind? This is a possible but not necessary conclusion. The most parsimonious explanation would probably be that the later drawings are less realistic because of the cumulation of simplifying memory effects and lack of skill. It is reasonabler though, to expect variations in the degree to which thought is primordial even in a laboratory situation. Primordial cognition does not mean only extreme states such as dreams and delirium, which are in fact not conducive to artistic production. Our thoughts are always varying to a slight degree along the conceptual-primordial axis (Klinger 1978; Singer 1978). It is exactly such slight variations that I have been talking about whenever I have claimed. that artists are creating in an altered state of consciousness. (Page 344)

- The series of responses to the sentence stem “A table is like ___ ” shows remarkable parallelism with what has occurred in French poetry since 1800. In order, the responses were:

- the sea, quiet

- a horizontal wall

- a formicaed [sic] bed

- the platonic form

- a dead tree

- a listening board

- versatile friendship

- vanquished forest

- a seasoned man

- two chairs

- The first three responses are based upon the flatness of the surface of a table. The fourth response mediates between these and the next two, which refer to the material composition of tables. All of these similes are clearly “appropriate,” suggesting a high level of stylistic elaboration: irrelevant responses were being filtered out. This filtering is discarded with the seventh response. The ninth and tenth responses clearly indicate a new, less elaborated “style.” The ninth response may be mediated by the word “seasoned,” which is transferred from wood to man: man and wood share a common attribute, although in a completely different sense; therefore they are compared. The tenth response is based upon the close associative connection between table and chair. Associative contiguity overrides objective dissimilarity–exactly as happened in twentieth-century French poetry. Presumably, subjects in the later trials could continue to increase originality only by lowering level of elaboration, by applying less stringent stylistic rules to their responses. (Page 347)

- The task of a scientist is to produce ideas. That wouldn’t be hard if it weren’t for the constraints. One of the most severe of these is that the ideas have to be true. More exactly, the ideas cannot be contradicted by empirical evidence. Furthermore, this constraint cannot be evaded by producing ideas that cannot in principle be tested against reality. Scientific ideas have to be falsifiable (Popper 1959). They have to be susceptible of being shown to be incorrect. This selection pressure is common to all scientific disciplines. Scientists are in the position of poets before the twentieth century, who had to produce realistic similes. Why don’t scientists discard this constraint and produce surrealistic science? In fact, this is just what mathematics has done. In its early stages, mathematics was an empirical science. The constraint for realism has long since been abandoned, so that mathematicians produce “theories” that do not necessarily correspond to any empirical reality. (Page 350)

- Can we make an analogous argument for science? I think that we can, but the pressure to increase arousal potential in science must lead in an opposite direction: toward less rather than more primordial thought. Broadly speaking, a poet’s task is to create ideas of the form “x is like y” where x and y are coordinate terms or concepts on the same level. Habituation of arousal potential forces successive poets to draw x and y from ever more distant domains. They seem to do this by engaging in ever more primordial thought over time. Scientists, on the other hand, have to produce statements of the form “x is related toy, ” where x and y are on different levels. (Page 354)

- These people formulate the general laws and develop the basic methods that define the paradigm. After the paradigm is established, normal science begins. Normal science is carried out by the members of what Crane calls an invisible college-a group of people who interact with each other and share the same goals and values. In the late stages of a paradigm, most major problems have been solved. This leads scientists to specialize on increasingly specific problems. This is necessary in order to extract the remaining ideas. In this stage, anomalies may also appear. In the final stage, there is exhaustion or crisis. The paradigm offers few possibilities and many problems or anomalies. As a consequence, members defect and are not replaced by new adherents. Very much the same thing happens in art and literature. A style gathers recruits who tend to know and interact with each other. There is excitement at first; but eventually the possibilities of the style are exhausted, and it becomes stale and decadent. Crane ( 1987) has analyzed the recent history of American painting in a manner analogous to her earlier analysis of science. (Page 358)

- A paradigm can die for two reasons. There can be exhaustion without anomaly: that is, the paradigm has succeeded too well, and there are no problems left to be solved, as happened to Euclidean geometry. After the time of Euclid, there was nothing left to be done. The fit with reality had become perfect. Although Crane does not put it in these terms, we could say that arousal potential fell to zero, and the field elicited no further interest at least in the sense of scientists wanting to work in the area. In the case of exhaustion with anomaly, a different set of affairs exists. The exhaustion is not perceived as such. What is perceived is that a fit with reality can be obtained only with very complex theories. Further, new ideas can be generated only with considerable effort. In addition, there are undeniable anomalies or incongruities. Complexity, effort, and incongruity are likely to cause negative affect. In contrast, a new paradigm- if it is to be successful- will be more attractive: the fit with reality is not perfect, but neither are anomalies present as in an old paradigm. Anticipated payoff in relation to effort is much higher.

The new paradigm usually wins by default. The old paradigm does not die. Its adherents die. Because they have not been able to recruit new disciples, the paradigm dies with them. Once this happens, the new paradigm becomes dominant, and the process begins anew. (Page 358)