A dear friend asked me to write down why I think that taking chances (“taking a leap of faith”) can often be a good idea even if you have no idea where that leap will land. To give credit where credit is due, these thoughts are heavily influenced by the writings of Stewart Kauffman, in particular, his book At Home in the Universe.

To start with, we need to talk about fitness landscapes. A fitness landscape is like most natural landscapes; there are hills and valleys. Some are more rugged, some are smooth. The higher you can get on a particular fitness landscape is the more suited you are for that particular domain.

Consider something like running. If you want to get faster, it helps to train. The more you train, the faster you get. Up to a point. Then things like specialized training, nutrition and rest all start to play a part. There is no direct line to running as fast as you possibly can. The fitness landscape for becoming a better runner is relatively simple, but it’s not a straight line:

This fitness landscape is pretty simple. There is a single, best peak. That is where you are fastest.

But there’s a catch. Where you start on this landscape is random. You may be born with a certain amount of running talent, but if you are raised somewhere that running is hard to do, then you may not realize the full extent of your natural ability.

Look closer on the chart. There are two high points. One on the left-most side, and one in the middle. If you start close enough to the left edge, then improving means moving left towards a high point that is less than what you are truly capable of. In this case you start “faster” than someone on the right hand side of the graph, but if they follow the slope as far as it goes, they will be faster in the end. This idea of an original position is a fundamental component in the concepts of fairness and justice. If you don’t know where you’re going to start in life, you shouldn’t have laws in the way of reaching your full potential.

If your fitness landscape is simple like this, then getting better is simply a matter of finding the way that leads up the slope of fitness. Once you find that path, it’s reasonably straightforward.

But what if your fitness landscape looks like this?

If you look closely, you can see that this is based on the same landscape as before, but it is far more chaotic. There is no good path to anything. One step along the landscape may be a huge improvement, but the next step could be catastrophe. There is no progress on a landscape like this.

But most of our experiences, both in the physical world and in less tangible domains are neither smooth or chaotic. They are rugged.

This is a world that most of us are familiar with. There are peaks and valleys, and a kind of roughness to the profile we see. Instead of just one or two peaks, there are several. This kind of terrain is fractal – as you zoom in or zoom out, the roughness doesn’t change.

Now, according to the concept of original position, we do not know where we will start on this landscape. Some of us are born in the valleys. Most start somewhere on the slopes. A lucky few start at the top.

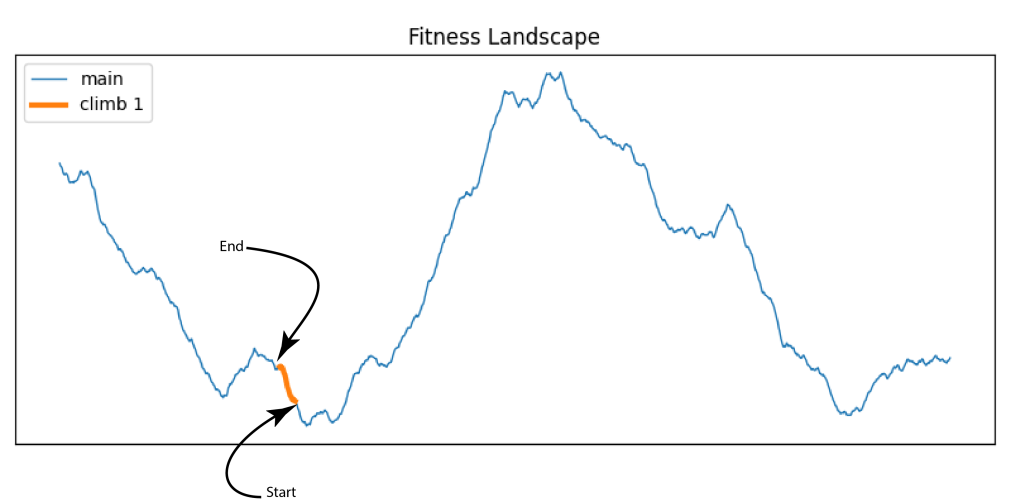

The hill climbing strategy for the smooth terrain won’t work here. We climb only until we reach a minor dip:

To get across these dips we need a certain amount of grit – the ability to push through problems and make it to the other side:

That gets us much closer to the local peak. Maybe even all the way to the top. But look at the landscape. We are among the foothills of true mountains! Hill climbing, even hill climbing with grit, can only get us so far. We need something else. Something disruptive. A leap of faith.

If we leap in any direction from out current peak, we will wind up on the slopes of a far larger mountain. Where we land initially may be lower than where we are, but here, the opportunity to climb is much better!

The likelihood that we will randomly start on the slope of the highest peak is not all that high. In this case, it’s about 20% that you’d end up on the green slope, which is the most straightforward way to the highest point in this landscape. But if you notice that your progress has stalled, some disruption in your life might move you to a more productive place.

These kinds of jumps often mean that you’ll land at a lower spot than where you leaped from. My friend, who’s adventures prompted this post was living in Portland Oregon with a nice life but felt stuck. Her leap was to move to New York City. She had a rough landing, but is working her way up a new slope (which has been lumpy and required grit) and enjoying the new opportunities she’s found. Her leap has paid off.

So if you’re feeling stuck, and have enough grit to persevere through tough patches, consider taking a leap of faith and disrupting your life. I felt stuck and got into a PhD program which put me on a completely new trajectory. Other people I know have switched careers, had a serious injury or disease. In many of these cases, after a period of initial struggle, they found themselves in better places.

And the thing is, if it seems like your leap isn’t working out you can always take another leap. Either back to the familiar place where you leaped from, or to a new unknown. I tried the New York City thing too, and was too young and inexperienced to make that choice work. So I jumped back to safety, recharged and then went out and found another path.

Have faith.

For those of you who are interested, here’s the Python code used to generate the figures in the text. Feel free to explore and see how your choices can work out 😉

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random

from typing import List, Dict

NAME = "name"

X_LIST = "x_list"

Y_LIST = "y_list"

def fractal_points(y_coords:List, offset:float, step:int) -> int:

print("Step = {}, offset = {}".format(step, offset))

x = int(step)

size = len(y_coords)

while x < (size-1):

i1 = int(x - step)

y1 = y_coords[i1]

i2 = int(x + step)

y2 = y_coords[i2]

y = (y1 + y2)/2

y_coords[x] = y + (random.random()-0.5)*offset

#print("[{}]({}), [{}]({}), [{}]({})".format(i1, y1, x, y_coords[x], i2, y2))

x += int(step*2)

step/=2

return step

def fractal_line(name:str, size:int = 1024, scalar:float = 0.5, offset:float = 10.0) -> Dict:

x_list = []

y_list = []

for i in range(size+1):

x_list.append(i)

y_list.append(0)

y_list[0] = (random.random()-0.5)*offset

y_list[size] = (random.random()-0.5)*offset

step = size/2

while True:

step = fractal_points(y_list, offset, step)

offset *= scalar

if step < 1:

break

return{NAME:name, X_LIST:x_list, Y_LIST:y_list}

def line_segment(lines_list:List, main_index:int, name:str, start:int, stop:int):

ld:Dict = lines_list[main_index]

xl = ld[X_LIST]

yl = ld[Y_LIST]

x_list = []

y_list = []

for i in range(start, stop, 1):

x_list.append(xl[i])

y_list.append(yl[i])

lines_list.append({NAME:name, X_LIST:x_list, Y_LIST:y_list})

def get_average_y(yl:List, index:int, dist:int) -> float:

val = 0

count = 0

size = len(yl)

start = max(0, index-dist)

end = min(size, index+dist)

for i in range(start, end, 1):

val += yl[i]

count += 1

if count == 0:

return 0

return val/count

def find_highest(lines_list:List, main_index:int, start_x:int, name:str, avg_dist = 1) -> float:

ld:Dict = lines_list[main_index]

yl = ld[Y_LIST]

x_list = []

y_list = []

cur_x = start_x

cur_y = get_average_y(yl, cur_x, avg_dist)

x_list.append(cur_x)

y_list.append(yl[cur_x])

step = random.choice([-1, 1]) # we dont want to bias our search direction

while True:

cur_y = get_average_y(yl, cur_x, avg_dist)

# print("[{}] = {}".format(cur_x, cur_y))

next_x = cur_x + step

next_y = get_average_y(yl, next_x, avg_dist)

if next_y > cur_y:

cur_x = next_x

x_list.append(cur_x)

y_list.append(yl[cur_x])

continue

next_x = cur_x - step

next_y = get_average_y(yl, next_x, avg_dist)

if next_y > cur_y:

cur_x = next_x

x_list.append(cur_x)

y_list.append(yl[cur_x])

continue

# if we get here, we're done

break

lines_list.append({NAME:name, X_LIST:x_list, Y_LIST:y_list})

return yl[cur_x]

def draw(lines_list:List):

f1 = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

frame = plt.gca()

frame.axes.get_xaxis().set_visible(False)

frame.axes.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

ld:Dict

line_width = 1

for ld in lines_list:

plt.plot(ld[X_LIST], ld[Y_LIST], label = ld[NAME], linewidth=line_width)

if line_width == 1:

line_width = 3

plt.xlabel("Location")

plt.ylabel("Fitness")

plt.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.title("Fitness Landscape")

def main():

random.seed(7) # Good: 4,5,6,7

size = 1024

max_attempts = 3

lines_list = []

ld = fractal_line("main", size=size)

lines_list.append(ld)

draw(lines_list)

# randomly pick a start

# prev_high = ld[Y_LIST][start]

# find_highest(lines_list:List, main_index:int, start_x:int, name:str, avg_dist = 1):

for i in range(max_attempts):

start = random.randint(2, size - 2)

cur_high = find_highest(lines_list, 0, start, "climb {}".format(i+1), avg_dist=25)

draw(lines_list)

# line_segment(lines_list, 0, "seg 1", 100, 200)

# line_segment(lines_list, 0, "seg 2", 500, 600)

# f1 = plt.figure()

# draw(lines_list)

#if we want to draw more charts

# f2 = plt.figure()

# draw(x_list, y_list)

plt.show()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()