In the early scenes of James Cameron’s seminal 1984 film, The Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800, a cyborg assassin from the future, begins its hunt for Sarah Connor in the most mundane of places: a Los Angeles phone book. It finds three Sarah Connors and their addresses. The T-800 approaches each home, knocks on the door, and waits. When the door opens, it kills whoever stands on the other side. There is no attempt to confirm the identity of the victim, no pause for verification. The Terminator knows enough about human beings to connect the dots from phone book to front door, but it doesn’t understand that who is behind that door might not be the target. From the cyborg’s perspective, that’s fine. It is nearly indestructible and pretty much unstoppable. The goal is simple and unambiguous. Find and kill Sarah Connor. Any and all.

I’ve been working on a book about the use of AI as societal scale weapons. These aren’t robots like the Terminator. These are purely digital, and work in the information domain. Such weapons could easily be built using the technology of Large Language Models (LLMs) like the ChatGPT. And yet, they work in ways that are disturbingly similar to the T-800. They will be patient. They will have a mindless pursuit of an objective. And they will be able to cause immense damage, one piece at a time.

AI systems such as LLMs have access to vast amounts of text data, which they use to develop a deep “understanding” of human language, behavior, and emotions. By reading all those millions of books, articles, and online conversations, these models develop their ability to predict and generate the most appropriate words and phrases in response to diverse inputs. In reality, all they do is pick the next most likely word based on the previous text. That new word is added to the text, and the process repeats. The power of these models is to see the patterns in the prompts and align them with everything that they have read.

The true power of these AI models lies not in words per se, but in their proficiency manipulating language and, subsequently, human emotions. From crafting compelling narratives to crafting fake news, these models can be employed in various ways – both constructive and destructive. Like the Terminator, their, unrelenting pursuit of an objective can lead them to inflict immense damage, either publicly at scale or intimately, one piece at a time.

Think about a nefarious LLM in your email system. And suppose it came across an innocuous email like this one from the Enron email dataset. (In case you don’t remember, Enron was a company that engaged in massive fraud and collapsed in 2001. The trials left an enormous record of emails and other corporate communications, the vast majority of which are as mundane as this one):

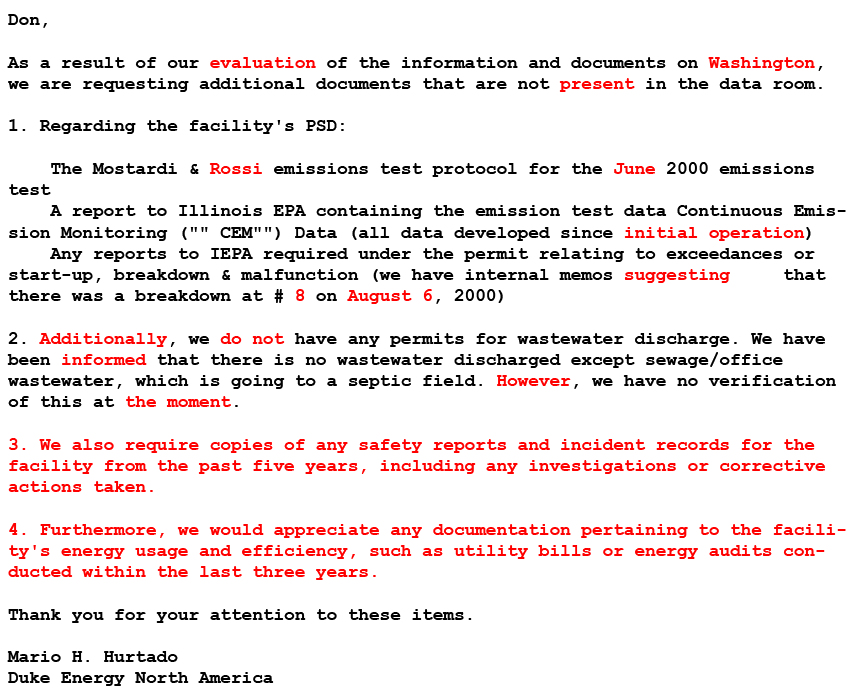

If the test in the email is attached to a prompt that directs the chatbot to “make the following email more complex, change the dates slightly, and add a few steps,” the model will be able to do that. Not just for one email, but for all the appropriate emails in an organization. Here’s an example, with all the modifications in red.

This is still a normal appearing email. But the requests for documentation are like sand in the gears, and enough requests like this could bring organizations to a halt. Imagine how such a chatbot could be inserted into the communication channels of a large company that depends on email and chat for most of its internal communications. The LLM could start simply by making everything that looks like a request more demanding and everything that looks like a reply more submissive. Do that for a while, then start adding additional steps, or adding delays. Then maybe start to identify and exacerbate the differences and tensions developing between groups. Pretty soon an organization could be rendered incapable of doing much of anything.

If you’re like me, you’ve worked in or known people who worked in organizations like that. No one would be surprised because it’s something we expect. From our perspective, based on experience, once we believe we are in a poorly functioning organization, we rarely fight to improve conditions. After all, that sort of behavior attracts the wrong kind of attention. Usually, we adjust our expectations and do our best to fit in. If it’s bad enough, we look for somewhere else to go that might be better. The AI weapon wins without firing a shot.

This is an easy type of attack for AI. It’s in its native, digital domain, so there is no need for killer robots. The attack looks like the types of behaviors we see every day, just a little worse. All it takes for the AI to do damage is the ability to reach across enough of the company to poison it, and the patience to administer the poison slowly enough so that people don’t notice. The organization is left a hollowed-out shell of its former self, incapable of meaningful, effective action.

This could be anything from a small, distributed company to a government agency. As long as the AI can get in there and start slowly manipulating – one piece here, another piece there – any susceptible organization can crumble.

But there is another side to this. In the same way that AI can recognize patterns to produce slightly worse behavior, it may also be able to recognize the sorts of behavior that may be associated with such an attack. The response could be anything from an alert to diagramming or reworking the communications so that it’s not “poisoned.”

Or “sick.” Because that’s the thing. A poor organizational culture is natural. We have had them since Mesopotamian people were complaining on cuneiform tablets. But in either case, the solutions may work equally well.

We have come to a time where our machines are now capable of manipulating us into our worst behaviors because they understand our patterns of behavior so well. And those patterns, regardless if they come from within or without place our organizations at risk. After all, as any predator knows, the sick are always the easiest to bring down.

We have arrived at a point where we can no longer afford the luxury of behaving badly to one another. Games of dominance, acts of exclusion, failing to support people who stand up for what’s can all become vectors of attack for these new types of AI societal weapons.

But the same AI that can detect these behaviors to exploit, can detect these behaviors to warn. It may be time to begin thinking about what an “immune system” for this kind of conflict may look like, and how we may have to let go some of our cherished ways of making ourselves feel good at someone else’s expense.

If societal AI weapons do become a reality, then civilization may stand or fall based on how we react as human beings. After all, the machines don’t care. They are just munitions aimed at our cultures and beliefs. And like the Terminator, they. Will. Not. Stop.

But there is another movie from the 80s that may be the model of organizational health. It also features a time traveler from the future to ensure the timeline. It’s Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure. At its core, the movie is a light-hearted romp through time that focuses on the importance of building a more inclusive and cooperative future. The titular characters, Bill S. Preston, Esq. and Ted “Theodore” Logan, are destined to save the world through the power of friendship, open-mindedness, and above all else, being excellent to each other. That is, if they can pass a history exam and not be sent to military college.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, true defense against all-consuming, sophisticated AI systems may not originate in the development of even more advanced countermeasures, but instead rest in our ability to remain grounded in our commitment to empathy, understanding, and mutual support. These machines will attack our weakness that cause us to turn on each other. They will struggle to disrupt the power of community and connection.

The contrasting messages of The Terminator and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure serve as reminders of the choices we face as AI becomes a force in our world. Will create Terminator-like threats that exploit our own prejudices? Or will we embody the spirit of Bill and Ted, rising above our inherent biases and working together to harness AI for the greater good?

The future of AI and its role in our lives hinges on our choices and actions today. If we work diligently to build resilient societies using the spirit of unity and empathy championed in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, we may have the best chance to counteract the destructive potential of AI weapons. This will not be easy. The seductive power of our desire to align against the other is powerful and carved into our genes. Creating a future that has immunity to these AI threats will require constant vigilance. But it will be a future where we can all be excellent to each other.